The Best Verses Never Used to Demonstrate the Truth of the Eucharist

Much of what Christians are asked to believe is not explicit in Scripture. In fact, some of what we believe is arguably not contained in Scripture at all. Questions about the canon of Scripture itself, the nature of biblical inspiration, who can write Scripture, when the canon closed, when a couple is joined in marriage, and by whom, is there on going public revelation, and more, are not contained explicitly in Scripture.

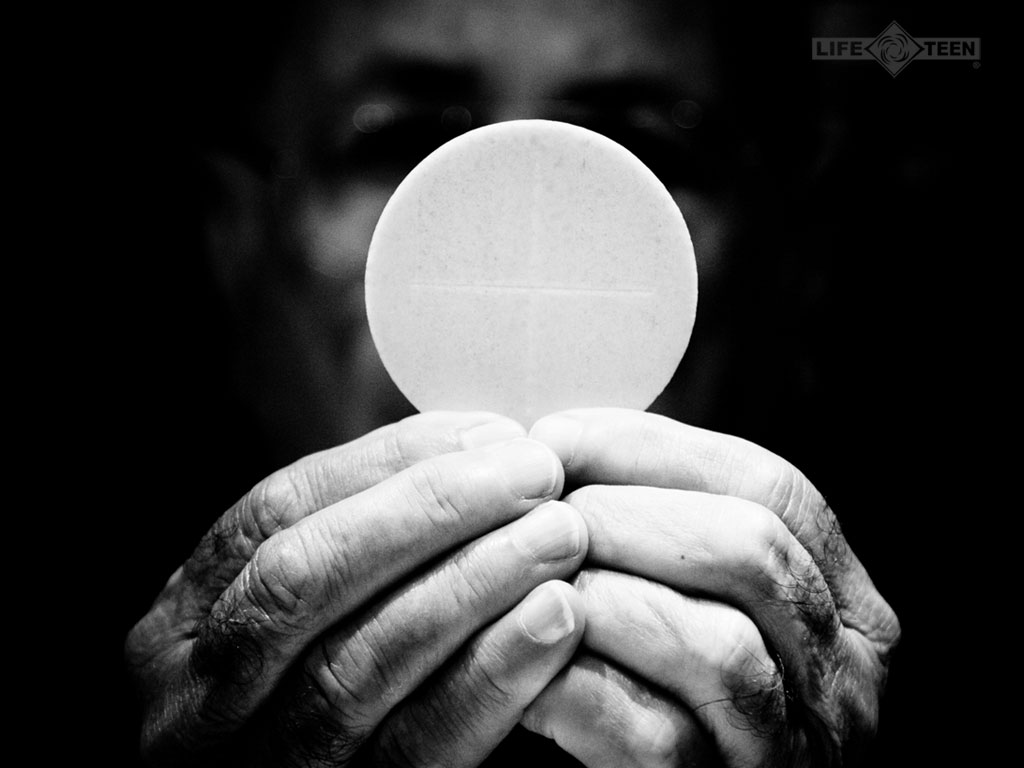

But the Eucharist definitely does not fall in the above category. There is much that is remarkably clear in Scripture about the Blessed Sacrament, especially concerning the real presence. The institution narratives, and, of course, John 6, and I Cor. 10:15-18 come to mind immediately. But in this post, I would like to deal with what may well be the plainest text of all. And if not the plainest, it is certainly the best text that is almost never used by Catholics to demonstrate the biblical foundation for the Eucharist: 1 Corinthians 11:27-29. I know many, if not most, would argue John 6 is the strongest text and they have a pretty good argument. But at any rate, here is I Cor. 11:27-29:

Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of the body and blood of the Lord. Let a man examine himself, and so eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For anyone who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment upon himself.

According to St. Paul, a constitutive element involved in a Christian’s preparation to receive the Eucharist is “discerning the body.” What body is St. Paul talking about that must be “discerned” you ask? It’s really not very hard to tell. He just said, in verse 27, “Whoever . . . eats . . . in an unworthy matter will be guilty of the body and blood of the Lord.” Any questions?

These very plain words were a stark reminder to the Corinthians 2,000 years ago, and should be for us as well. We must recognize not just what it is that we are receiving in the Eucharist, but who it is: Jesus Christ.

And there’s more!

St. Paul uses unequivocal language in describing the nature of the Eucharist by using the language of homicide when he describes the sin of those who do not recognize Christ’s body in this sacrament and therefore receive him unworthily. He says they are “guilty of the body and blood of the Lord.” According to Numbers 35:27, Deuteronomy 21:8, 22:8, Ezekiel 35:6, Rev. 18:24, 19:2, and elsewhere in Scripture, to be “guilty of blood” means you are guilty of shedding innocent blood in murder. This is not the language of pure symbolism. This is the language of real presence.

Think about it: If someone were to put a bullet through a picture of a real person, I am sure the person represented in the photo would not be thrilled about it, but the perpetrator would not be “guilty of blood.” But if this same perpetrator were to put a bullet through the actual person you better believe he would be “guilty of blood.”

Thus, the language used here in 1 Corinthians 11 is very strong—some of the strongest language St. Paul could have used, in fact—to underscore the truth that when he says we must “discern the body” here in the Eucharist, he means we must “discern the body” here in the Eucharist! This is conclusive evidence of the real presence of our Lord!

Objection!

Many, especially our Lutheran friends, might see and even cede the point of the Real Presence here but then point out that St. Paul also refers to the sacrament as “bread:” “Whoever eats this bread and drinks this cup . . .” Even if someone agrees to the real presence here, could this statement of St. Paul’s point more to a Lutheran notion of consubstantiation, rather than transubstantiation? In other words, even if Christ is present here, wouldn’t Paul’s reference to the sacrament as “bread” prove the “bread” is also present “alongside” the body and blood of Christ?

It does not come as a surprise to Catholics that St. Paul would refer to the Eucharist as “bread” and “wine.” We do it commonly in the Church. This is so for at least two key reasons. First, Jesus is “the true bread come down from heaven” and “true drink” according to John 6:32 and verse 55. It is entirely proper to refer to the Eucharist as such because the Eucharist is Jesus. Second, in human discourse we tend to refer to things as they appear. This is called “phenomenological” language. We say “the sun will rise at 5:45 am tomorrow.” Does this mean we are all geocentrists who believe the sun rotates around the earth? I hope not!

We find examples of phenomenological language in many texts of Scripture as well. Daniel 12:2 in the Old Testament and Acts 7:60 in the New Testament refer to death as “falling asleep.” I assure you there is an essential difference between dropping dead and taking a nap, but the inspired authors use this language because it was and still is common to do so. When someone dies, his body looks like he “fell asleep.” Thus, the dead are often referred to as having “fallen asleep.” When it comes to the Eucharist, it retains the appearances of bread and wine; it should be expected that it would be referred to at times as it appears.

A Critique of “Consubstantiation”

The problem with consubstantiation boils down to two central points:

1. It attempts to claim Christ is “really present,” but then denies a truly bodily (physical) component to that presence. That makes no sense. If Christ is merely “spiritually” present, which is what consubstantiation suggests, then he is not wholly present. Christ can “appear in another form” as we see in Mark 16:12 when he appeared to Clopas and the unnamed disciple on the road to Emmaus, but if it is truly and really Christ—body, blood, soul and divinity—there must be what Pope Paul VI called in his great Encyclical Letter of Sept. 3, 1965, Mysterium Fidei, a truly “physical” reality to our understanding of that “true presence.” Otherwise, there would be no real distinction between that presence and the presence of Christ in his word or in us as Christians.

2. Consubstantiation ultimately denies the word of Jesus Christ who said, “This is my body . . . This . . . is the new covenant in my blood” when he instituted the Eucharist in Luke 22:19-20. “Consubstantiation” claims Jesus was still holding bread and wine in his hands—even though it also claims a sort of undefined “real presence” alongside the bread—but Jesus declares the “bread” and “wine” to be his body and blood. Unless we are having some trouble with the meaning or use of the word “is” Christ’s words in context are very clear. Christ is presenting himself as the New Covenant “lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world” who must be consumed in order for the people of God to participate in his saving sacrifice (John 6:53). This is the language of the real presence, including the bodily part, not the language of either consubstantiation or pure symbol.